Keren Cytter

Repulsion

19.5. —

4.7.2010

The artist Keren Cytter (*1977 in Tel Aviv, lives and works in Berlin) is by now familiar in Switzerland. For years she has been represented by Elisabeth Kaufmann Gallery (now in co-operation with Christiane Büntgen), and her first Swiss solo exhibition in 2005 took place at Kunsthalle Zurich. The following year Cytter won the Art Statement Award. In addition, her works were shown in solo exhibitions at Frankfurter Kunstverein (2005), Kunst-Werke Berlin (2006), MUMOK Vienna (2007), Witte de With, Rotterdam (2008) and at Le Plateau Paris (2009), as well as in numerous group exhibitions worldwide. Last year, the artist was nominated for the prestigious Preis der Nationalgalerie für junge Kunst in Berlin. Cytter studied art in Tel Aviv and Amsterdam. She is best known for her experimental video works that illuminate the interpersonal and the private, works that are often based on templates of literary or cinematic classics, simultaneously reflecting the influence of the media. The artist is also concerned with drawing, theater production, performance, dance, and even writes screenplays and novels.

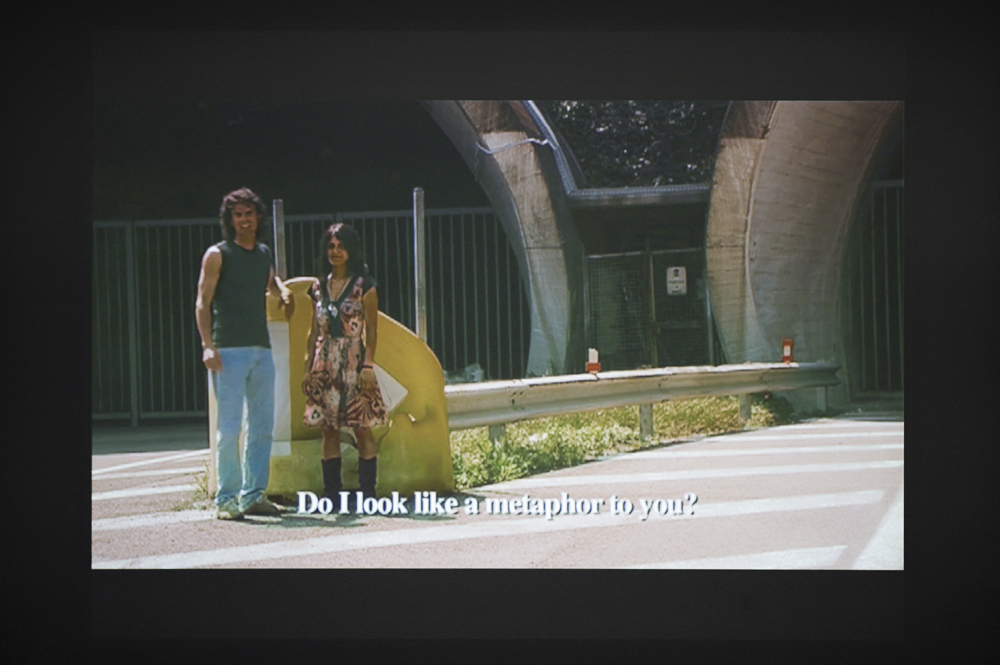

The exhibition Repulsion at Kunsthaus Baselland, named after one of her works, presents a selection of videos that have not yet been seen in the Swiss institutional framework. Among the recurring stylistic elements in Cytter’s videos — in addition to extensive references to cinema and television — are long monologues and numerous vocal overlays, with sound and image usually not synchronized. The image of a male actor can be superimposed with a female voice; a simultaneous subtitle in turn refers to another thing entirely. Cytter, who writes all the scripts herself, uses language according to the particular mood or atmosphere that she would like to generate: French is used for example as the language of love, and English as a pragmatic language. At times, notes or stage directions on the particular filmic work find a self-referential way into the spoken language. A further separate level of language consists of the subtitles that appear to coincide with what is said, though the content may actually differ. Shorter loops and both verbal and visual repetition may appear within the usually not longer than ten-minute films. The artist decomposes the film into its normally determined components in order to independently reassemble them again: (amateur) actor, role, voice, spoken word, listened text, language and subtitles are put together in an unusual mix, mostly asynchronous to each other. With her strategy of deconstruction Cytter points out how our perception is dependent on certain speech and image structures and shows that there is a kind of intentional perception that delivers content by using ‘nuances.’

The three-screen, synchronized video work Repulsion (2006) was created after Keren Cytter encountered the olfactory and unpleasant conditions in the apartment of a friend while watching Repulsion by Roman Polanski. The title of the film met by chance the situation. As a consequence, the artist turned the emotions of disgust and revulsion into three short films. The focus is on the feelings and relationships between a protagonist and two supporting actors, which in the course of action lead in each case to different scenes of death. Cytter focuses primarily on those moments in which the protagonist is alone, being completely at the mercy of emotions of disgust and repulsion. The three film scripts written by the artist and filmed with friends within three days come together in a symmetrical relationship: The characters change parts – the killer in one movie is the victim in the second, and the witness in the third, and so on. After editing the films, the artist soon realized that the repulsive starting point was not to be found in its original intent and that the films evoke different emotions.

The film Les Ruissellements du Diable (literally “The whisper of the devil”, 2008), is based on the short film of the Argentine filmmaker Julio Cortázar Las babes des Diablo (1958); another reference is the film Blow Up by Michelangelo Antonioni shot in 1967 (again is based on Cortázar). The dialogues of the two main characters, a man and a woman, are not synchronized or don’t exist, while in-between the credits appear, confusing the viewer about the end of the film. The temporal discrepancy apparently obliterates all actual and fictional: the female protagonist is simultaneously an actor and TV presenter who stages her alter ego as an erotic fantasy. Alternating, the man and the woman tell the story, with the man speaking in the third-person singular and the woman in the first-person. Again and again a meeting in the park and an enlarged photo of this meeting take centre stage. The superimposed narrator characterizes the two translators as amateur photographers — thus people who work with language and image and who have the facility to change them in subtle ways. The metaphor of translation, whose specific set of problems is an important part of the film, is driven further in so far as the French dialogue is subtitled in English. Amidst all of these sounds and images appears a frontal close-up of a man masturbating. One might, like Skye Sherwin does in ArtReview, conclude that in “Les Ruissellement, reality is unstable, art the only certainty, solipsism unavoidable, and consequently masturbation the only thing that seems truly, graphically and physically ‘real’.”

The films Alla ricerca di fratelli/In Search for Brothers and Forza che viene dal passateo/A Force from the Past (2008) deal with Italian clichés. The Italian film of the 60s serves as a reference, especially those of Pasolini and Fellini. In the films, amateur actors from Trento acted at locations that served as the social meeting places of the city. The various viewpoints regarding moral and religious beliefs of the characters form the content of these stories. Film thus becomes a collage of places, locations, characters, stories and texts.

The film Untitled (2009), produced for Venice Biennial, is based on the true story of a boy who shot the mistress of his father out of jealousy. For the making of the film, Cytter worked with both professional (Bernhard Schütz, Carolin Peters) and amateur actors. Inspired by the film Opening Night (1977) by John Cassavetes, Untitled was filmed in front of live audiences at the Hebbel Theatre in Berlin. The main character is a woman who is about to act on stage and at this very moment starts to think about her own life and her own identity — both the real and the ‘acted’ one. In light of the theatre stage and the presence of an audience, the ambiguity of reality and fiction gains a particularly strong emphasis. By help of specific camera settings, Cytter focuses on the psychological moments of the story — the feelings of hatred, fear and anxiety are especially in high gear. In certain moments, the different perspectives of the camera create the impression as if we ourselves are moving with the actors. Sometimes, observation itself is shown to us quite plainly — particularly when the live audience becomes our mirror.

Text by Sabine Schaschl