Über die Metapher des Wachstums

21.5. —

10.7.2011

The international exhibition project On the Metaphor of Growth is a cooperation between the Kunstverein Hannover, the Frankfurter Kunstverein and the Kunsthaus Baselland. Each of the three exhibitions place a different accent on artistic dealings with the concept of growth, demonstrating its present-day ambivalence in economic, biological and social contexts.

The concept of ‘growth’ is overall rated positively and the act of growing itself is considered a desired process. Generally we like it if something is growing: flowers, our children, our capital, the gross national product, the pensions, and of course the economy altogether. Growth has become a civilising guide value that is closely related to a deeply rooted belief in progress, since the existential problems of humankind seem to be solvable thanks to the development of technology and civilisation. In this way genetic technologies promise the optimisation of agricultural production and pharmaceutics. Engineering sciences have visions of a sustainable energy supply through innovative technologies, and in space travel, the accessibility of the remotest planets. Digital technologies accelerate exponentially, and in information technologies in the meantime one talks about a gigantic knowledge explosion. The possibilities grow and expand; boundaries are overcome or seem to merge into infinity. Growth is confirmed as the right formula of human development, where each growth is followed by another.

If, based on the deliberations of Prof. Bernhard H.F. Taureck, one follows the concept of growth as a metaphor borrowed from biology, one encounters another side to it, which is mostly negated in its metaphorical usage. Organic growth is always determined by a natural boundary, it understands the state of being fully grown and is characterised by a cycle of growing and decaying.

Particularly in the course of crises the question of the limits of growth becomes obvious: when the atomic catastrophe of Fukushima destroys the vision of unlimited and harmless energy, when the recent economic crisis shatters the belief in permanent value increases, when malign cancer cells grow, when forecasts on the increase of the world population or on the development of the global climate sketch a gloomy future for our planet. It’s not only in scientific circles, but also in the feuilletons that an increasing scepticism about permanent growth is voiced for some time now. Growth is not up to date anymore, is the current chorus. A ‘new scepticism of growth’ can be found and now there is talk of a ‘humane market economy’, as well as of ‘wealth without growth’. The call for a modest and prudential handling of natural resources and raw materials becomes increasingly insistent.

In the sphere of cultural production the reasoning of growth as a central principle of social organisation has for quite some time been an important topic. On the basis of exemplary phenomena artists use the concept of growth and its related belief in progress as an opportunity for examinations and visualisations. Their perspectives and work modes aim at growth as a metaphor and in the process often operate themselves metaphorically.

Text by Holger Kube Ventura, Sabine Schaschl, René Zechlin

The video Modern Relics (2008) by Marisa Argentato & Pasquale Pennacchio (IT, born in 1977/1979, living in Berlin) refers to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s famous film La Ricotta (1962). It tells the story of a film production on the Passion of Christ and at the same time relates the dissipated and corrupt life on and behind the film set. Pasolini’s issue was the falsity of the cinematic illusion compared to the reality of its production — which, however, also only exists in the film. In the opening scene of La Ricotta, one sees two men stripped to the waist dancing to a popular song in front of an abundantly set table. In the video of Argentato & Pennacchio, precisely this scene is shifted to an illegal Italian rubbish dump. Pasolini’s overladen table reminiscent of a 17th-century still life is replaced by remains and scraps, modern leftovers, perhaps the dangerous waste of modernity. In the work Do it just (2008), the artists focus on the trade with copies of branded goods and contrast the need of ownership of the consumer with the damages to the economy. Nine Nike jackets, each with different symmetrical patterns, were forged in a company in Naples. Argentato & Pennacchio focus on production conditions and contexts of work, money and value creation and thereby the associated promise of a further development of the individual.

The works of Michel Blazy (born in 1966 in Monaco, lives and works in Paris) are shaped by their experimental and often ephemeral character. The materials he uses for his paintings, sculptures and installations are either taken from nature or stem from DIY stores, gardening markets and supermarkets. Blazy exposes them to natural decay processes that trigger processes of growth in the form of moulds. For example, when he waters a field of potato flakes treated with food coloring, he does determine the basic setting of the installation, but other factors such as humidity, lighting, temperature or the biological processes of the respective materials themselves contribute to the work’s appearance. His pieces are based on factors that are uncontrollable and subject to chance, and the duration of a show is usually determined by the extent to which the processes remain visible or the point in time when they are halted. Since the 1990s, the artist has also been experimenting with bubble bath, which he has used for a number of sculptures and installations. Within the framework of the exhibition On the Metaphor of Growths, both the Kunstverein Hannover and the Kunsthaus Baselland will exhibit bubble-bath installations. Put in garbage cans or rain barrels, gushing forth from walls or sets of shelves, the dense foam continuously grows to a form that simultaneously dissolves again. The sculptural appearance of the installation describes a state of permanent change, in which becoming and fading form a close cycle. The vessels Blazy employs, such as rain barrels or garbage cans from which the foam gushes forth, serve as receptacles for masses that are used up, processed and filled again in everyday use, as well. The incessantly emerging foam visualizes in an all but paradigmatic way the natural cycle of the metaphor of growth. In a further work presented at the Kunsthaus Baselland, Michel Blazy treats a wall with a mixture of agar-agar and food coloring. The gelling agent used in Asian cuisine breaks up over time and causes ‘peeling processes’. The wall frowns and ages — like skin after a sunburn or the bark of an acacia tree.

In addition to painting, the artistic activities of Max Bottini (born in 1956 in Bürglen/CH, lives and works in Uesslingen/CH) mainly concentrate on dealing with foodstuffs, their origin, preparation and social relevance, as well as with processes of nature and the way they are artistically conveyed. In numerous projects and actions, he focuses on the natural and social components of food and eating. From April to September 1994, for instance, a project was realized in which chickens — especially raised, organically fed, meticulously weighed, and professionally slaughtered — were ultimately prepared according to a recipe from Hong Kong and served to invited guests under the Thur bridge in Swiss Thurgau. Bottini was primarily interested in the rituals revolving around eating, the passing down of recipes, culinary experiences, and the table as a place of conversation. A further large-scale project at the Kunstmuseum Thurgau (2000–2001) consisted in collecting and tasting 1,100 foods stored in bottling jars, with the possibility of exchanging senses of taste and recipes, which lent the work its communicative and process-oriented character. For the show at the Kunsthaus Baselland, Bottini conceived a project in which the growth of a so-called Golden Vivax bamboo is meticulously tracked. He places the bamboo in the outdoor space of the Kunsthaus Baselland and attaches to the top of the shoot a thread leading to the inside with a pencil at the end. Like marking the growth of children, usually on doorframes or concealed parts of the wall in the parents’ home, the artist turns the flourishing of the plant into a visually traceable process. Bottini’s actions and installations frequently employ well-known procedures that, artistically treated as research methods, sensitize the viewers in a new way.

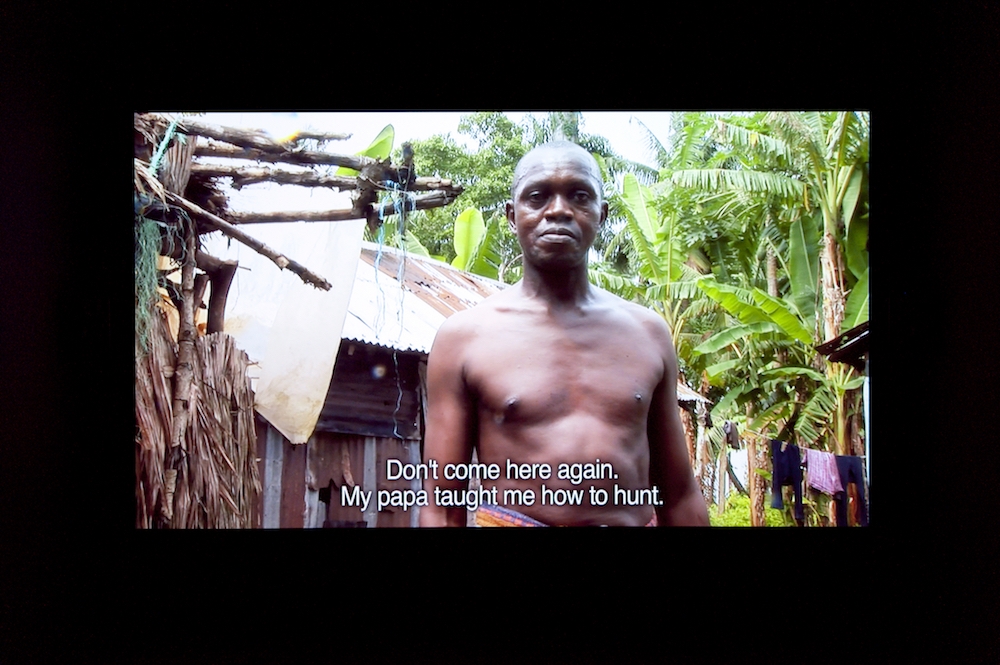

Mark Boulos (USA, born in 1975, lives in Amsterdam) addresses the relationship between religious fundamentalism, ideology and terrorism in his works. He travels through regions difficult to access or societal enclaves, where he collects documentary film material that he then edits in a poetic or radically exaggerated way. The resulting films and video installations experiment with the potential socio-critical uses of these media: Mark Boulos’ works do not confront the viewer with linear documentations but instead with the filmic process of analysis, interpretation and evaluation. In his two-channel video installation All that is solid melts into air — a quote from Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto — he spatially juxtaposes two worlds. One side depicts militant Nigerian resistance groups in the Niger delta, one of the world’s most important oil-producing regions. Boulos spent several weeks there and draws a disturbing picture of local resistance against the oil-producing plants of foreign corporations. Oil production has brought no economic progress to the region whatsoever, quite to the contrary. It has lastingly destroyed the populations subsistence farming. Boulos’ video installation describes the aggression of Nigerian fishermen who in face of the exploitation of their land and the loss of their livelihood through water pollution have resorted to arms. The other side of the two-channel projection portrays the global trade with oil as a resource at the international exchange in Chicago. Mark Boulos shot the material for this video at the time when the US-American Bear Sterns Bank collapsed, which was followed a short while later by the international credit crisis in 2008. Just like the oil-producing location in Nigeria, the site of value-creating trade with this resource on the market is depicted as a theatre of war: His video presents the battle of the brokers, their speculating frenzy to gain advantages in face of volatile quotations of the value of oil. In the form of a poetic parable, Boulos compares two phases of oil as a commodity on its journey through the capitalist world order: from its production in the swamps of the Niger delta to its economic dissolution on the electronic information walls in Chicago. In the artist’s view, both sides are determined by battles and the associated rituals, by belief in war deities and in material and immaterial fetishes. In the installation All that is solid melts into air, Boulos focuses both on the status of the actors’ self-presentation and the always presumed authenticity of the documentary material. The perfectly synchronized films on both screens start with media-related and cultural clichés, to then all the more strongly stress the elements of truth that they bear.

Some of the works presented in the exhibition On the Metaphor of Growth deal on an abstract level with the theme of elementary, seemingly natural growth. Artists, such as Peter Buggenhout (Belgian, born 1963, lives in Gent) produce work that in its material and form conveys the sensual experience of the principle of growth and decay, evolution and disintegration. His sculptures are pieced together from discarded building materials and scraps of trash, for example the wood of a former fishing boat, the metal strips of an old set of blinds, or the plastic piping of a replaced waterline — and are coated with unusual organic matter. In the works from the series Gorgos, horsehair and pig’s blood are used, among other materials, and the strange surfaces of the works from the Mont Ventoux series are created with the use of dried cow stomachs. In the series The Blind Leading the Blind — which immediately recalls Pieter Bruegel’s famous painting by the same title — the artist covers his sculptures with a thick layer of grey-black domestic or industrial dust, which is then affixed to the sculpture in a complex procedure. The same is true of a large work with the number 35 from the year 2010. At first this appears to be the burnt remains or foreboding sign of a catastrophe, such as the leftover, piled up debris from a collapsed building. The monstrous remains of the New York World Trade Center after the attack are forced to mind: massive, buried, and cracked building elements, which are held together by cooled molten liquids emitting odd scents and covered by a thick layer of dust. The surfaces of Buggenhout’s sculptures alternate between an indescribable, sometimes apocalyptical chaos and finely chiseled structures. Only in a few places — and there quite evidently — do the works reveal their precise sculptural design. They are neither ensembles of found objects, nor vestiges, nor organically formed clumps. The sculptures seem to adhere to a logic inherent to both the elements from which they are composed and the conditions of their placement in space, a logic also residing outside of them, in the mind of the creator. Precisely because they refer to nothing more than themselves, to the viewer they are always experienced as entities. They have character and expression, great presence and individuality, and they are as much technical as organic formations. Although one can sometimes identify the origin of their individual components, the sculptures are void of allusions, autonomous; these objects are not sculptural representations; they entail no elements of narration, let alone symbolic references. In this sense Peter Buggenhout uses the phrase ‘abject things’, that is, things that refuse any form of identification, also as art objects. Achieving this strange unique quality, and not a specific form, is the aim of Buggenhout’s artistic working process. Materials are sculpturally piled on top of each other, fitted together, and worked in a painterly manner, until a certain degree of abstraction has been achieved that precludes any inherent possibility of symbolic reference. Precisely for this reason could Buggenhout’s works be understood as metaphoric visualization of the principles of growth and decay, evolution and disintegration. For all their morbidity and radical contrariness, these sculptures appear as manifestations of universal growth and the inexorable principle of life.

In her first exhibition in 1990, Sylvie Fleury (CH, born in 1961, lives in Geneva) presented what appeared to be the spoils of a shopping spree under the title C’est la vie: Meticulously lined up, shopping bags and boxes of luxury brands stood on the floor of Gallery Rivolta in Lausanne. The things that were possibly hidden in these bags became the object of Fleury’s art a few years later: Gucci shoes, Louis Vuitton purses and Chanel perfume flacons were exhibited as chromium-plated bronzes in museum display cases or on gallery plinths covered with fur fabric. She also made gold-plated bronzes out of trivial objects such as shopping carts, wastepaper baskets or ladders, and even turned car wrecks into attractive objects by presenting them in the season’s trendy nail polish colors. Fleury does not merely exhibit popular brands and labels but also produces art work (commodities) that promise to satisfy the exact same desire. In this regard, it is the tyranny of desire and not the critique of consumerism that she actually demonstrates to the viewer with each new work of art. As both a fire raiser and fire fighter she relies on the effect of shining, high-quality surfaces such as gold, silver and chromium that lend even the most banal object a special aura. “The idea is to use something that has been manufactured in the hundred thousands and suddenly leave your mark on it, a sign that simultaneously signifies the sense of belonging to a clan, a culture or an identity-forging community, i.e., to a group different from the masses. They are buttons of rebellion.” (Sylvie Fleury) In sculptures such as Ladder (2007), Yes to All (2004) and Ela 75k (Go Pout) (2000), the artist cites simple objects of everyday use with a rather short lifespan and contrasts their profanity with materials such as bronze and gold that stand for endurance on account of their value and durability. Not only statues were cast in bronze for eternity but also tablets of law — in the Roman Empire, for instance. Gold has always counted as the most precious metal and it played an equally important role in earlier cults surrounding gods and rulers as it does today in the times of financial crises and volatile markets as an apparently secure investment. The bronze cast and gold-plating turn ladder and wastepaper basket into expensive and rare art objects that only the wealthy can buy. Although the utility value of the refined ladder and basket is retained, their exchange value on the art market and their potential of distinction and increase in value are now at the fore. Sylvie Fleury’s artworks are not exhausted by their mere purchasability but additionally promise intellectual satisfaction — even in the case of a Louis Vuitton purse, the possibilities of use are probably less decisive than the feeling of elevation that it may give the person carrying it. Purchasing these luxury articles as well as such artworks can satisfy similar desires. Yet the precondition is the possession of considerable financial resources. In other words, in order to be able to buy the golden shopping cart, one must have successfully climbed the career ladder beforehand.

Tue Greenfort (born 1973 in Holbæk/DK, lives in Berlin) deals with relations between man and nature and the impact of human activities on the ecosystem, particularly on energy and material cycles. With his sculptures and installations, he draws attention to problem areas that result from growth processes. More than being a criticism of environmental pollution or a guidance to resource conservation in the context of art, these are rather politically charged, aesthetic injunctions that operate with references to minimalism and conceptual art. His sculpture 1 kg PET (2007), a molten pile of plastic from 29 polyethylene terephthalate bottles, focuses on the proportionality of production, use and consumption of resources. PET bottles were introduced in the 1980s in the food industry, particularly successfully for the sale of drinking water. Due to their lightness and lower transportation costs, they were considered as an environmentally friendly alternative to glass bottles. But PET cannot be easily recycled into new bottles, as it does not achieve adequate transparency on melting. Thus huge amounts have to be newly produced constantly to meet the demand. Greenfort bases his reasoning on the following facts: The production of 1 kilogram of PET requires 17.5 kilograms of water and entails the harmful emissions of 40 g of hydrocarbon, 25 grams of sulphur oxide, 18 g carbon monoxide and 20 g of dioxide. The production of a PET bottle accordingly requires more water than they can ultimately hold, and in doing so additional pollutants are released. The work Hungry for more (obesity starvation) (2008) consists of disposable bags with printed smiley, as used in many Asian fast food shops in New York. Greenfort has welded together the bags into a structure into which a fan blows air in or out. This creates a ‘breathing’ context. While the smiley is especially wide on an inflated bag, it shrivels together when the air is sucked. In this work the artist deals with the discrepancy of the increasing numbers of obese people worldwide with a simultaneous increase in the number of the starving. In 2006 Professor Popkin of the University of North Carolina presented before the International Association of Agricultural Economists figures which show that there are 300 million overweight people facing 800 million undernourished people. In 2007, the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations) speaks of 923 million chronically hungry people and traces the causes, not least to the rising food prices. The object of the inhaling and exhaling Smile Pocket becomes a kind of memorial, which is reminiscent of the element types of all human needs and their unbalanced distribution in the world. The work From Petroleum to Protein (2007/2011) is based on an article in the Scientific American of 1965, in which the extraction of edible protein from crude oil is described. The transformation was carried out by means of bacterial processes and was first tested in a factory by BP at Marseille. The experiment was intended to facilitate the food supply for the rising world population. After several years of tests in which animals were fed with these proteins, the project was discontinued after the apprehension of cancer as a follow-on effect got out of hand. Greenfort exhibits the journal with the original article in a display case, as well as a recent experiment set-up erected by the Cantonal Laboratory Basel-Country. In the process, a fungus (Candida tropicalis) with paraffin (from the diesel production) was set in a glass container. The objective here too is the production of protein based on the scientific article. Greenfort in this work focuses on the question that is valid today more than ever, on food supply for the increasing world population and with the exemplary approach points out how much research and work goes into this search.

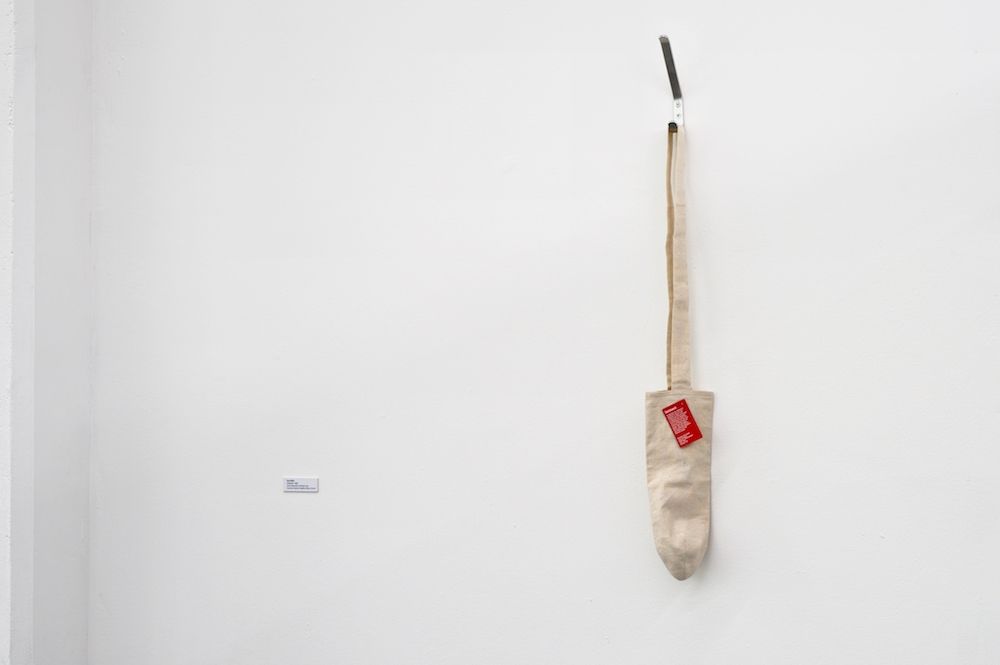

San Keller (born in 1971 in Bern, lives and works in Zurich) likes to call himself a ‘service providing artist’. His art usually manifests itself in the form of actions in which he looks into and questions human conduct and the way in which both the art system and society work. One of his best-known actions is titled San Keller schläft an Ihrem Arbeitsort (San Keller Sleeps at Your Workplace), which he performed for the first time in the year 2000. The work consists in the agreement that the artist will sleep at the client’s workplace, even when he or she is working. The fee for sleeping there amounts to the average daily wage of the client. The action has since then been ‘purchased’ by different employers and evoked a wide variety of responses in the media and the public. To treat something allegedly inactive such as sleep as a payment in kind was regarded as a provocation by many. In the exhibition On the Metaphor of Growth in Basel and Hannover, San Keller presents his work Mein Kontostand (The State of My Account) (2005). Originally created on the occasion of an exhibition at Galerie Brigitte Weiss, the artist published the state of his current account on a daily basis the way it appeared on the bank statement. In the Kunsthaus Baselland, the work will be extended insofar as table mats printed with daily account balances are placed in restaurants around the exhibition building during the week of the Art Basel (15 to 19 June 2011). San Keller will have his lunch each day at a restaurant and then bring the used mat back to the exhibition. The traces of the food and the value appreciation of artistic works on the occasion of the art fair are thereby brought into focus. The picture frame which is designated solely by the relevant date of the planned action at the beginning of the exhibition is supplemented during the period 15 to 19 June 2011 by the daily account balances of the artist. At the Kunsthaus Baselland, also the audio piece Blow Up (2005) and the object Geldsack (Money Bag) (2004) will also be exhibited. When purchasing the money bag, the owner undertakes to fill the bag before traveling to any poor country with coins of the local currency and distribute them to beggars there — coin by coin until the bag is empty. The works that take up the theme of money usually evoke particularly emotional reactions on the side of the recipients. Accumulating and losing money, either physically or displayed in print, can be read not only as an individual but also as a general metaphor reflecting the societal goal of permanently increasing the amount of money. In his work Blow Up, San Keller acoustically renders the bursting of the ‘bubble’ in a direct way: When playing the CD, one hears the sound of a balloon being inflated — until it bursts with a loud bang.

Sebastian Mundwiler (born 1978 in Arlesheim, lives and works in Basel) was trained as a perennial and coppice gardener and he studied art. Both fields are combined in Mundwiler's performative actions. For the exhibiton On the metaphor of growth, he conceived a guided botanical tour in the immediate vicinity of the Kunsthaus Baselland. The plants on location are the starting point of reflections on the interplay of man, urban space and nature. The boundaries between cultivated nature and rank growth are often not clearly defined. On the one hand, Mundwiler highlights the site-specific circumstances influencing the plants' growth, on the other, the civilizational side effects that secure the survival of the plants. Therefore, the places that Mundwiler visits on the tour are not laid out by urban or landscape gardeners, but are instead sites where nature appears alien or even as an intruder. In direct proximity to the Kunsthaus Baselland, the city and rural cantons meet. The banks of the Birs River, separating the two cantons, are shaped differently on the urban and rural side-depending on the canton's decision. While on the side of the Baselland canton one can find tall trees, wild undergrowth and footpahts of ground and stones, the urban side of the path is asphalted and plant growth is strongly regulated. The artist is not interested in the politically caused discrepancy but in examining human behaviour and perception, which he does by directly engaging with the perspective environment.

In her video works, Julika Rudelius (born 1968 in Cologne, lives in Amsterdam and New York) deals with human behaviour, communication codes, and cultural and gender-specific patterns of conduct. The places precisely defined for her shootings are often specially created, as for her video installation Economic primacy (2005). Here, an ordinary office serves as the setting for a conversation between five men selected by the artist. A lawyer, a media consultant, a PR consultant, a millionaire, and a top manager answer questions raised by the artist that are inaudible to the viewer. In their monologs, the men declare money and the increase in profit to be the only objective and at once the driving force behind all their activities. In a disturbing manner, the work describes economic growth and the pursuit of profit as the preconditions of power and influence. The starting point of the piece is Rudelius’ investigation of a list of identifying psychological features of psychopaths. The artist sees parallels between the description of these symptoms and the communicative behaviour of the successful businessmen, for example, the lack of empathy or the manipulative use of language.

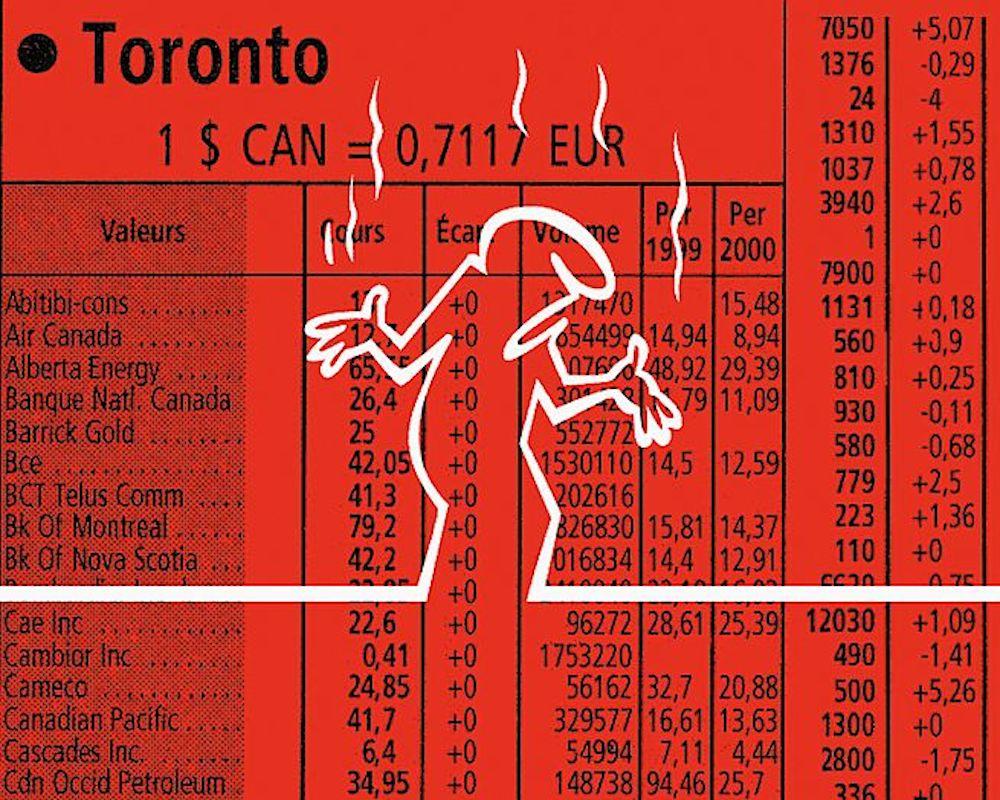

The work of Franck Scurti (born in 1965 in Lyon, lives and works in Paris) is characterized by everyday life. Aspects of the consumer world, of an international, urban lifestyle culture and the associated music scene have an influence on his works. Scurti relates them to the concept of ‘street credibility’, a term from the music industry meant to confirm that rappers are respected and considered credible in the streets, where rap once originated. When the artist draws on individual motifs of everyday life, he also conceptually and consciously adopts the connotations of the term and the socialization connected with the object. His object Sandwich (1998), for instance, reproduces the door of a bakery in his neighborhood along with the attached label and the list of accepted credit cards. A further example is the piece Street Credibility (1998), for which the artist had his shoes resoled with the motif of the Parisian city map. In the exhibition “Über die Metapher des Wachstums” at the Kunsthaus Baselland, Scurti shows the video La Linea (2002), for which he produced a new episode of the eponymous cartoon series in agreement with its creator, Osvaldo Cavandoli. The animated film consists in a single line from which the figure and its direct environment emerge. The series is characterized by the direct dialog between the cartoon figure and its creator, who reacts by gradually drawing and changing elements of the surroundings. For the background of his two-minute episode, Scurti used graphics from the business press showing rising and falling share prices and which he interprets as a kind of economic landscape. His version of the cartoon series addresses the interplay of artistic production, creativity and the market, comparing phenomena in business and art. The existence of the figure is set in direct relation to economic motives, with the artist and the art product literally pulling in the same direction.

Lois Weinberger (born in 1947 in Stams/A, lives in Vienna) “is working on a network, devoting his attention to peripheral areas and questioning all sorts of hierarchies. He sees himself as a field worker and started in the early 1970s with ethno-poetical works, which are the basis for an artistic debate — developed over some decades — concerning standard social behavior in both natural space and that of civilization. Ruderal plants involved in all areas of life, are initial and orientation point for notes, drawings, photographs, objects, texts, films as well as big projects in public space”(www.loisweinberger.net). His installation at the Kunsthaus Baselland within the framework of the show On the Metaphor of Growth, takes up an early draft from the year 1991. For the competition “Kunst & Raum St. Pölten (government sector),” Weinberger conceived a steel cage marking a free space outdoors for the uninhibited growth of plants. This “ruderal enclosure” was originally intended for various locations both in landscapes and urban space. “Wild Cube — Ruderaleinfriedung” (2010), the title of the installation at the Kunsthaus Baselland, consists of three steel cages, drawings, sketches and photographs having to do with this concept, which was realized seven years after the competition draft in 1998/99 as a 40-meter-long cage with steel bars at the Neue Sozial- und Wirtschaftsuniversität in Innsbruck. The permeable grating allows plant seeds to both enter and leave the enclosure, inside which whatever lands there can grow. “Against this background, the gardens of Lois Weinberger, in which plants and the ground are to a large extent left to themselves and weeds are revaluated, in which the green migrates and neophytes are out on parole, appear almost visionary. They are the radical forerunners and a paradigmatic example of more recent parasitic and symbiotic strategies in dealing with nature.” (Susanne Witzgall)

What is visible — the grating — is conceived as an enclosure / for a space / created out of a precise carelessness toward / what is generally called nature. Furthermore and essentially it is a work about becoming and fading — all the way to our invisible nature / the nature of the mind.

Fallows / peripheries / that our urbanization efforts push ahead of themselves / are gardens / in which the borders show themselves as something that leads on— that moves — that is insecure.

Gardens of variety left to themselves correspond with present-day urgencies / the noticing of breaks / connections and their vibrations / to see the garden as a sign of voluntary abandonment / of composure / of non-intervention. And yet a second hand nature all the same — the extent to which we approach nature / it vanishes.

Hence, reforestation will be left to the wind / the birds / the seeds that are in the earth anyway — spontaneous vegetation — a gap in urban space — WILD CUBE. (Lois Weinberger)

Andreas Zybach (born in 1975 in Olten/CH, lives and works in Berlin) frequently addresses issues from the area of research in technology, biology or architecture in his works. Zybach transfers the observations and studies of these sciences to conceptual artistic considerations that range all the way to current socio-political themes. For example, a NASA concept for the construction of a space station from the 1960s serves as the starting point of the work Rotating Space (2004). Researchers in astronautics such as Wernher von Braun made attempts to create artificial gravity to establish conditions similar to those on earth. To this end, the researchers developed a circular space station that produced the required gravity through internal rotation. In a way comparable with greenhouses and botanical gardens, in which a controlled environment is also produced, Zybach seeks to combine the two approaches in his installation of steel, soil, water and plant seeds. On the inside, his rotating reconstruction taken from space travel research refers not only to the actual growth of plants but also to the lasting human vision of being able to limitlessly expand mankind’s habitat on earth. The installation Ohne Titel (Architekturmodell), first realized in 2003, addresses spatial, architectural growth. For the exhibition at the Kunsthaus Baselland it is expanded in a site-specific and content-related manner. Sheets of paper in landscape format on which calls for action are printed are cut up in reading direction by a paper shredder. Zybach thus undermines the actual function of a shredder: The machine doesn’t cut up the information until it can no longer be read, but instead neatly separates the text line by line. When visitors pick up a strip of paper from the growing pile created by the shredding process, which is controlled by a timer, they are confronted with sentences such as “Please take this along,” “Please rip this up,” “Throw the contents of your bag on the floor,” or “Please leave the room.” Andreas Zybach thus adds a communicative level to his work, initiating a variety of mini-performances. The artist says: “It is the attempt to deal with social questions such as authority and autonomy — also in the context of producing works of art. If there are enough people interested in an idea or a problem, this often results in a spatial implementation. Partially to architecturally represent the diversity of this community to the outside, partially to conceal the problem(s) to be solved.”