Laurent Montaron

Pace

21.1. —

21.3.2010

Laurent Montaron (born 1972 in Verneuil-sur-Avre, lives in Paris) is regarded as one of the most interesting upcoming artists of a younger generation both in his native France and abroad.

His solo shows at Kunstverein Freiburg, at Institut d’Art Contemporain in Villeurbanne/Lyon, at FRAC Champagne-Ardenne, his solo presentation at last Frieze Art Fair (Schleicher+Lange Gallery) and numerous participations in international group exhibitions have placed his work firmly into the European discourse. Montaron works in various media: film, video, photography and sculptures, as well as sound installations. The focus of his interest is the exploration of visual representation codes: Montaron questions the relationship and the conflicts between image and reality, of each narrative and its interpretation.

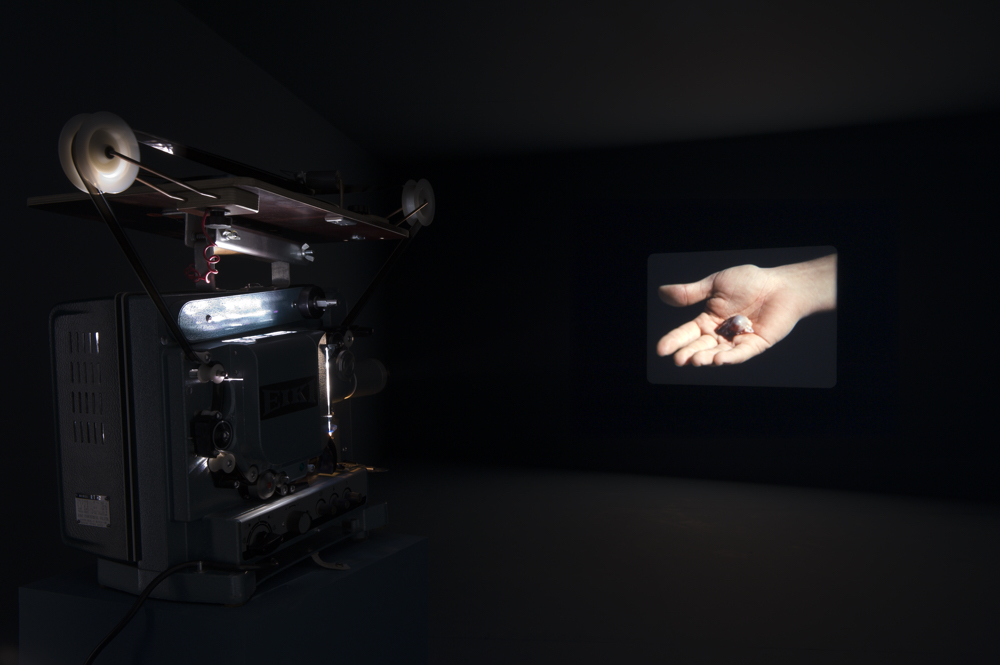

The exhibition at the Kunsthaus Baselland is entitled "Pace", named after the film installation of the same title. Pace is a 16mm film projection behind a wall and a stained glass window, which shows the beating heart of a carp held in the palm of a hand. The slightly insulated noise of the projector and the vibrating of the heart freed from the body form an acoustic symbiosis; the window emphasizes the voyeuristic element in the observation of the image. Montaron examines in equal measure the unpleasant and the beautiful, but leaves open whether this is a ‘real’ or a ‘fictitious’ image.

The HD film Will There Be a Sea Battle Tomorrow? (2008) is based on the social and scientific recurring interest in supernatural experiences. A machine from the Institute for Parapsychology in Freiburg, called Psi-Recorder, is in the focus of the film. This device is able to generate random numbers that can be used for experiments that investigate the phenomena of telepathy, clairvoyance, and foreshadowing. The question “Will There Be a Sea Battle Tomorrow?” is based on the logical innovations of Greek philosopher Diodorus Cronus, who developed theses on future contingents, provided that neither is necessarily true nor absolutely false. The philosopher maintained that only those things are possible which actually are or will be; hence everything which is not going to be cannot be, and all that is, or is going to be, is necessary. Consequently, Laurent Montaron’s film is about the question of whether our future is preordained, or whether a premonition is consistent with an exact science. He discusses the phenomena of time and chance, and he raises fundamental questions that, although unanswered, present a poetic disposition.

The light installation How is it that this long night is interrupted? (2008) addresses the issue of randomness. Two identical light bulbs are symmetrically mounted on a wall. A light switch affixed nearby releases electrical impulses to the one or to the other illuminating the respective bulb. To generating the random impulses, the artist uses an electronic chip that was invented in 1960. Laurent Montaron’s interest in equipment and instruments from a pre-computerized, bygone time is constantly palpable. Thus, the anvil D (2010) at the entrance to his exhibition appears as a visual code that refers to a completely different time, in which hooves were shod or other rectangular or round shapes were hammered. The object bears the engraved inscription: “Is not this what we like to believe rather than being left to the night?”, a phrase from the video “Will There Be A Sea Battle Tomorrow?”. Montaron opens the exhibition with a general matter of belief, which also applies to art: Do we want to believe it, or do we prefer to leave it to the darkness of the night? The title is in turn the result of a tuning fork’s coordination with the anvil — thus a thoroughly verifiable measurement unit that nevertheless contributes nothing at all to the interpretation of the work.

Two photographs in the first room of the exhibition show a man with long hair playing a dulcimer. Dulcimer Player in Front of a Shotgunhouse (2010), the title of the photo sequence, is reminiscent of film footage. The slightly different snapshots are closely linked in time. At a closer look, the temporal elements prove to be even more complex: The dulcimer is originally an instrument from the Middle Ages. It was picked up in its almost unchanged medieval form in America and until today is especially used in folk music. While playing, the musician on the photographs records his play immediately with an older recorder. The Shotgunhouse, typical in the American South, is a visual remnant from the periods between the Civil War (1861-65) and the 1920s. Visual codes from different times and with different connotations meet and thus determine the contents of image sequences.

Another instrument, which until now is common in jazz music, is the electromechanical Hammond B3 organ (or Leslie Organ, named after the Leslie speaker). Montaron uses such an instrument for his installation Doppler (2009), which doubles and distorts a strange, almost insane laughter. Shown in the cold shed roofed space of the KHBL, the absurdity of laughter intensifies, which is used in one place and at a time that provides no logical motives.

Montaron’s most recent work, shown for the first time in this exhibition, integrates a phonograph, which plays upon request and with manual control a specially created capstan. Phoenix (2010, working title) raises the question of representation and perception mechanisms. What does a hardly usable music player mean today? To which musical era did it belong? What happens if together with the instrument an inscribed and attributed genre of music disappears? In many of his works, Montaron juggles science and belief systems, between logic and intuition. With machinery and instruments from a bygone era, with specific objects and poetic songs, he suggests much while the mystery remains. In all this, the spatial presentation of his works is of particular importance. Laurent Montaron’s works entangle the viewer in perception and interpretation issues. They are neither documentary nor fiction. They deal with the strategies of indication and of concealment, leaving the spatial presentation to play an important role.

Text by Sabine Schaschl