Histories of our Time

On collective and personal narratives

13.9. —

10.11.2019

The exhibition thus unites, on one hand, the major topics of our time, from Brexit to Trump, the distribution of power, migration, surveillance, gender (in)equality, moving personal biographies, to our approach to the world and foreign cultures, etc. On the other hand, the artists exhibiting show us a way through these major, pressing issues; a sensual, emotional entry point can be found to these issues that can help define one’s own attitude. The goal of the exhibition is not a comprehensive survey of such topics but rather the possibility of a precise artistic perspective on some selected subjects of great importance to the artists, or an opportunity, given one’s own background and biography, to challenge, contextualise and position oneself.

The 13 artists invited from the Basel region, Switzerland and beyond engage with just such questions and histories. Discussing how one’s own family history, for example, marked by surveillance, immigration and a new beginning, echoes on for a whole generation (Zoe Leonard); to what extent the rediscovery of already ‘rejected’ historic pictures might define a different narrative for a country or even a time (William Jones, Sabine Hertig); or how anger as well as bewilderment and powerlessness regarding a country’s political alignment and decisions, such as the current Brexit discussions, can clearly be expressed in a few words (Hanne Lippard); and how violence against women and international justice or injustice and lack of freedom can be presented with a high emotional charge, and how the distribution of power and strength is generally between the sexes within a society (Maja Bajević, Dorian Sari, Artur Żmijewski, Katja Schenker). Other topics include how (art) history has been told to date and how we think of passing it on (Anna Ostoya); and how trained, or indeed ignorant, our view of countries, cultures and the memory of a place is, and how we might nonetheless understand and read the other, the new and the unfamiliar despite the knowledge we lack (Cécile Hummel, Anna Molska, Piotr Uklański).

At the centre of the exhibition lie these diverse artistic tales, personal narratives and engagement with recent history as forms of gaining (emotional) understanding. The exhibition comes about in collaboration with CULTURESCAPES, which this year focuses on Poland, among other partners.

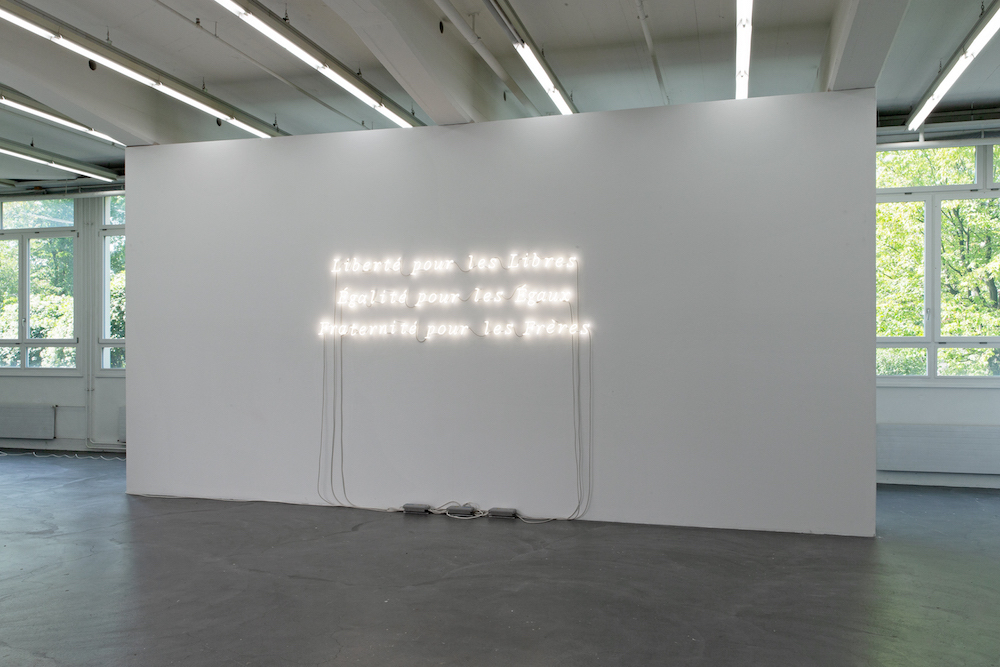

Maja Bajević applies various media to pose razor-sharp questions for our time, such as discussions of gender and women’s roles in society, globalisation, the distribution of power, violence, exploitation, neoliberalism and more. She also intensively considers the meaning and constitution of home, a topic that relates to the artist with her French-Bosnian background. A woman is continually touched by a man’s hand, humiliated and harassed (How Do You Want to Be Governed?); a neon sign that queries whether the fundamental French principles of liberty, equality and fraternity apply in practice to every single one of us; a series of drawings and collages which, like splinters of history, look back to the 1950s and ‘60s, relating seemingly to different news pictures and archives. How, in hindsight, do we read images in which a generation once believed with hope? Through narrating and focusing on particular examples, Bajević fans out a complex picture of our contemporary society, posing the question once more of how each individual behaves, positions themselves and thus actively participates in society. (IG)

The three works Landscape 13-15 belong to the largest black and white collages that Sabine Hertig has ever realised. She joins thousands of cut-out image fragments with glue on large canvases, creating a net of images, indications and associations. A seemingly impermeable world develops before our eyes and at the same time draws us under its spell. The formal image language contributes to the appeal of these picture landscapes as does the precisely arranged graduation of diverse grey tonal values and their implied light sources. From a distance, the analogue collages almost resemble an oil painting. As soon as one approaches them this effect disappears and the images shows all their constituent parts — yet do not lose their cohesion. Fragments of animals, naked bodies, nature and architectural elements are shown in all three works. Move to a distance again and the individual pictures come together as an almost apocalyptic scenario in which severed body parts, wildcats and wrecked boats develop their own idiosyncratic narrative. The artist’s sources include used Du issues, but equally other printed photography that has been written into our collective image memory and that now — in both their fragmentation and re-composition — may remind us of the pictures of the 1950s and ‘60s. Might this very way of dealing with the past be emblematic of the blurring boundaries between yesterday and today and the well-nigh piecemeal writing of history now? (JF)

For decades Cécile Hummel has explored countries, cities, their structures, rhythms and signs. She regularly exposes herself to the foreign and unknown and uses both a compact camera and a sketchbook to fix this — her — way of reading a city or a country. These researches, which can take the form of sketches, gouache painting or photography, subsequently gain various forms of medial translation, often complemented with found objects.

The installative, almost sculptural presentation of her photographs on long textile hangings in the exhibition is even reminiscent of an urban environment – of washing, hung up to dry in the open, and narrow byways to meander through. Observing the large-format photographs one becomes aware too, that Hummel is leading her audience right through the urban structure of a Mediterranean, European or Arab city. The artist brings the North African coast to meet Sicily on the other side.

The selection exhibited is part of a larger collection of images which Hummel unites in the magazine Recueil, which she established. How can the contemporaneousness of the image narratives be experienced in installation form? Can all the signs within — given whatever cultural background we each bring to it — be read at once? How close can the foreign be, how well-known can places be that we travel through regularly or others, where we have never yet set foot? Hummel’s urban photography, which she brings from her many travels and stays, subtly and delicately challenges our understanding of cultural and national histories. (IG)

William E. Jones’ series comes from the archive of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a support programme that was created in 1937 to help small farmers, at the time of the Great Depression. Photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Gordon Parks were commissioned with the documentation of farmers’ woes. As director of the FSA Information Division, Roy Stryker was responsible for the selection of the illustrations published. In order to mark a photograph as unsuitable, he punched a hole in the negative: Killed Portraits. Up until 1939 there were around 3,000 black and white negatives in all that appeared to have been lost for decades. Stryker’s criteria for his selection are unknown. Why were these pictures deemed inappropriate? Which (American) history was to be told?

In his series, Jones offers these photographs a visibility, the photographs which were never considered for publication. His interest lies in the photographers — named in brackets in each case — who, through one person’s decision, had been rejected and seemed destined to disappear. Just as the photographs became omitted information, through the black punched holes a gap appears in the formal, immediate pictorial context. Sometimes these happen in faces, sometimes just a point in the landscape. In his almost eight hour-long video entitled RejectedJones shows numerous such photographs with these holes, which are inevitably reminiscent of bullet holes. Using a continually varying zoom in onto 3,048 holes, the eye seems to get lost. The artist thus refines our understanding for what is visible and its flaws. (IT)

What significance can one’s own biographical lines or even past events acquire for the general public today? In her highly personal photograph series Zoe Leonard investigates this very question. Re-photographed photographs from her own family archive and her mother’s context form the basis of this, photographs which were taken before, during and after WWII. The maternal family came from Poland; some of them belonged to the Polish resistance and were thus persecuted, driven out and, in several cases, killed. The few that survived had to leave their homeland and were subsequently stateless and rootless for more than 15 years. Leonard is not interested in reconstructing this family history through her photographs, but instead she looks at the fact of statelessness and homelessness across generations and how it reverberates with us today – and whether we encounter it, directly or distantly. How do we deal with questions of displacement, exclusion or inclusion and the loss of homeland today? How do we position ourselves in relation to these issues and do these questions — which are existential for many people — touch our stories at all? In her works Zoe Leonard is neither accusatory nor loud, but she clearly shows how history repeats itself — and the short-sightedness in relation to subjects that are (now) recurring.

Hanne Lippard uses language as the starting point for her works: printed texts, sound installations and performances. Her main interest lies in communication and the different forms in which information can be received, but equally (mis)understood. Political questions and the question of the female voice in society play an essential role. In the exhibited work Brexistential the sentence ‘How to fix it’ appears, repeated several times, while the ‘it’ moves ever more towards the right-hand edge of the picture. The customary flow of reading is disrupted by the sentence changing to ‘How to fuck it’, which, in turn, also changes. The sentence ‘How to ex….it’ brings it to an end, though the ‘it’ seems to have been coughed out of the sentence structure. Lippard comments on the current political situation without stating the obvious and underlines her statement with the typographic arrangement. The ‘it’ that has fallen out of the sentence becomes emblematic for the United Kingdom’s agonising exit from the EU and the lasting ignorance of the whole significance of the decision. In parallel, in the work Modern Spanking, the artist’s voice sounds from two speakers: politely, softly and in a moderate tempo. She replaces the word ‘banking’ with seemingly endless other adjectives, which make the terms laughable, lend them an ironic undertone or allow them to appear naturally in a familiar context. The monotony of the repetition is disrupted and the voice becomes a poetic auditory experience. As Lippard once phrased it: ‘Every word when said with the right tone can become a piece of poetry.’ (JF)

The large spatial installation composed of five different videos seems like a visual and yet sensory conundrum. A scene in a flower shop, a convoy of black limousines or an almost unparalleled hydrographic phenomenon: a river bifurcation in Poland. What connects these subjects? What do these short looping clips tell us about a country and about those who look at the installation?

Polish artist Anna Molska leads the visitors through a labyrinth of images and sound that could not be more ambiguous. She sustains a state of confusion in the audience, and while they move through the unexpected, an unsettling experience crystallizes. The staged quotidian through which the viewers walk seems, at a certain point, to tip into irritation. Which forces drive us in which directions here? Yet it’s worth asking too what the filmic narratives by the artist about a country — in this case her homeland, Poland — tell us, and how what is shown here might be transposed to other places and narratives. (IT)

In the series Autopis. Notes, Copies and Masterpieces, (2010/19) Anna Ostoya reflects on avant-garde concepts in art from the early 20th century to the present and questions the authority of historical narratives. She reconsiders the role of women within the avant-garde, and analyses both central and peripheral phenomena in historical and geographical terms. Ostoya employs a pseudomorphic method, which entails the pairing of visually similar elements to forge new interpretations. The term Autopis is invented. In different languages and scenarios it can bring diverse associations, the notion of something self-written or perhaps mobile; a urinal, an autopsy, or utopia. The prefix auto suggests a thing or phenomena that is one’s own, spontaneous or automatic.

It is clear that the fight between the two battling men in Dorian Sari’s video work A&a(If art fails, thought fails, justice fails,…) is defined by its imbalance. That both figures are naked underlines the particularities of each. In an empty space the pair seem exposed; the whole situation seems bizarre and artificial.

The underdog is being used as a training object, strangled and pushed to the ground. Gratification for the already top dog, who sees himself confirmed in his dominant role. This kind of dynamic can be observed today all too often in political or societal relationships. Powerful authorities apply the advantages they are given to raise their profiles, or also in order to humiliate those lesser than them. In these real encounters, however — unlike here — transparency is missing. First shown at this year’s Swiss Art Awards, where it was prize-winning, the video work unsparingly reveals the starting point of many current conflicts.

Dorian Sari dedicates this work to artists from third world countries who have been expelled from Switzerland. (IT)

With her performative works Katja Schenker lends a form to the elusive feeling of bodies, their weight and power, and in so doing creates artefacts in the form of sculptures and drawings as well as works that tell the traces of the movement and what has happened. Forteresseis based on a performance first realised in 2010 in Lucerne. In it, the artist is surrounded by a 1.2 metre tall clay wall, around the outside of which is wrapped a cord. Through a slow, constant pull on the cord from within, the wall is — with the application of immense force — slowly pulled apart, layer by layer, in a spiral form, before coming together again directly, thanks to the material’s own weight. Through the action, a trace is left drawn upon both the outside and the inside of the clay surface. The object shown in the exhibition, which the artist had fired afterwards, represents a kind of witness, an artefact that tells of a past action. While the lines marked on the outer skin of the sculptural work still accord with a regular design, the inner walls show signs of the enormous amount of energy employed. Time is also a central topic repeatedly engaging Schenker, such as in the large wall work Wie tief ist die Zeit (How Deep is Time) (CutS05) which accords with a long cut through time and nature, akin to archaeological findings. A lasting query for Schenker is how a body changes over the course of time, how it marks itself on its surroundings and what remains of all human actions after they are gone. (JF)

The work The Disappearance of Steve Bannon is part of a large research project by artist Jonas Staal on the propaganda art of Steve Bannon, entitled Steve Bannon: A Propaganda Retrospective (2018). Bannon is mostly known as an ideologue and Donald Trump’s campaign manager. But from 2004 onwards he was also a prolific filmmaker who created ten documentary film pamphlets in a style he terms ‘kinetic cinema’.

Bannon’s films are deeply apocalyptic and propagate a notion of ’cyclical time‘: every four generations patriotic leaders must face enemies such as cultural Marxists, terrorists and the globalist elite in epic wars of civilisation to defend his vision of white Christian economic nationalism. In Staal’s project he analyses Bannon’s nearly fifteen years of film to explore how the core ideology of Trumpism was shaped by his propaganda cinema. Cultural change, the artist argues, precedes political change. Propaganda artist Bannon imagines, through his cinema, the core narratives and symbols of Trumpism even before Trump enters the political stage. While Bannon shows the imaginative power of art to change politics, at the same time he becomes its victim. After the new administration had been in office for a year, Trump grew frustrated with the power the media ascribed to Bannon. And when his propaganda artist made critical comments about Trump’s son Don Jr, the president broke ties with him and stated publicly that Bannon’s role was never important. In this artwork, Staal translates Trump’s removal of Bannon from his past by erasing Bannon from photos in which they appeared together. Like the Stalinist regime removed political opponents from official photographs, Trump also rewrote his own history. Just as art historian Boris Groys once spoke of ’The Total Art of Stalinism,’ the total art of Trumpism destroys those that once created it.

Accompanying the photographic work in this exhibition is the catalogue of Staal’s complete research project.

Major topics have long defined the work of artist Piotr Uklański: (pop) culture, collective memory, stereotypes and clichés, often with an ironic or critical undertone. His works frequently generate controversial reactions from audiences, or are even rejected. The photographs shown here from 2015 belong to the larger, 50-part series ‘Polska’ in which Uklański explicitly dealt with Polish mythology and iconography. They almost appear like an echo of the pictorial language from history books of the 19th, 20thand early 21stcentury. Untitled is stated under all five photographs, yet the subtitles in brackets give us indications of the monuments and memorials pictured, such as for victims of WWII, casualties of a shipwreck, etc. Through these we see, amongst others, the heroic figure of the Greek goddess Nike in a crown of leaves, she who embodies victory, as the personification of the heroes of Warsaw and Poland. A mistily romantic sunset is markedly dulled by the barbed wire setting of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial. Much more than provoking, photographs like these raise questions of the impossibility of representing the Holocaust or comparable decisive events of human cruelty in pictures. ‘There is no truth in representation’ states Uklański. To expose oneself to reality and its truth — without flinching — is an important criterion in the artist’s work. (JF)

In the Polish city of Wrocław (formerly Breslau) German cemeteries were rebuilt as parks in the 1960s and ‘70s, such as the Park Zachodni (West Park) where individual German gravestones can still be found today. In Artur Żmijewskis’ video Recovered (Odzyskane) the strategy of doing away with memories of German Breslau is told in documentary form.

Gravestones with German names are dug out by heavy machinery, transported away and used as the material for an (unusual) pavement in the Kozanów area of the city. By turning over the gravestones and the accompanying disappearance of their inscriptions, they apparently lose their meaning. At the same time they become politically charged objects that relate to German-Polish history. A play on the volatile situation in post-war years is also explicit in the video work’s title. The term ‘recovered territories’ relates to the displacement of the Polish frontier from the east towards the west, with which German Breslau became Polish Wrocław after the capitulation — with the consequence that German inhabitants had to give way. The approximately five-minute video by the Polish artist thus directly communicates a sense of unease, while passers-by walk over the stones with audibly speedy steps or a buggy is cumbersomely pushed over them, especially as the gravestone shapes have been maintained. Żmijewski emphasises the programmatic idea of ‘winning back’ the Polish city, which was also revealed in his other works such as Erasing (2016). While the work relates to the time directly after WWII, it is significantly contemporary — now that questions of identity formation, migration and cultural heritage are topics of discussion. (IT)

Selected press coverage

Basellandschaftliche Zeitung, 12.9.2019

Basler Zeitung, 14.9.2019

Basler Zeitung, 26.9.2019

Radio X (Oslo Night)

BZ Basel (Oslo Night)

Basellive (Oslo Night)

Kunstbulletin 11/2019